Listening to a recent BBC podcast, the Charitable Impulse, spurred me to write my first blog piece. In the podcast, David Edmonds draws upon new research regarding the psychology behind charitable giving, providing insight into the best ways for charities to gain support and donations. All the evidence combined suggests that if a testosterone fuelled pack of men were to chase after an attractive female, and ask her the right questions, then large donations to charity would follow.

A problem in the sector

Firstly, Edmonds addresses the lack of faith apparent in the media with regard to charities. It is rare that we object to the work of charities considering the vast and varied work they do for the less fortunate. Yet the death of Olive Cooke last year caused a stir, with many people complaining to the FRSB. It saddens me greatly that her death was linked to the charity sector, an impressive force in society today. It definitely raises a question about the ways in which charities operate.

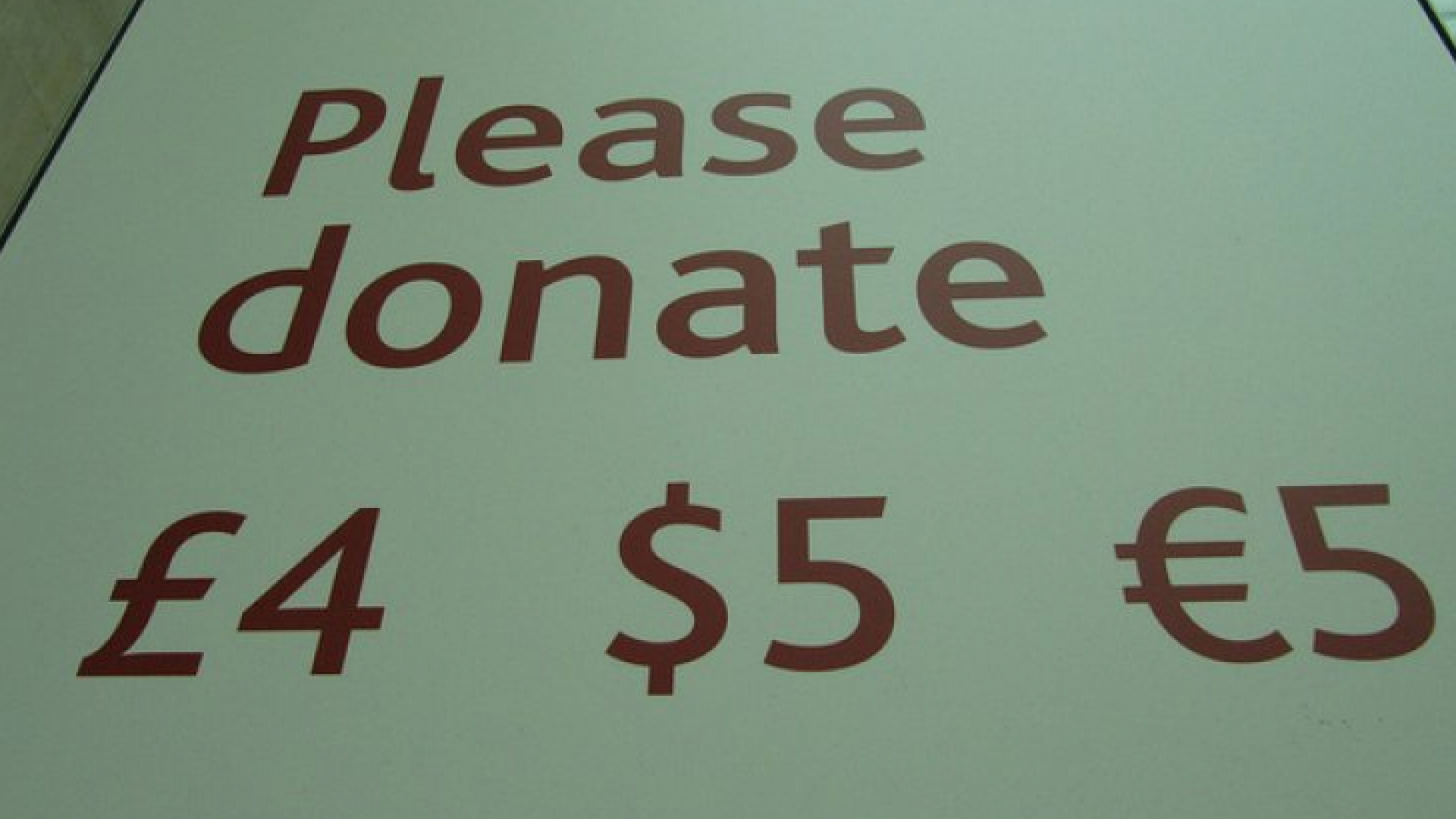

But despite these concerns, as revealed in our ‘Trust in who?’ blog last week, trust in charities has increased from 48% in Autumn 2015 to 55%. And in 2014 the UK donated £9.4bn to charitable institutions, ranking the UK among the most generous. So what is it that motivates us to donate? And how can this knowledge be used in the charity sector?

Led by emotions as opposed to reason

A main theme in the podcast is the role that our emotions play in decision making, in particular in charitable giving. Take, for example, an advert with a video of a child living in poverty, with wide eyes and a big smile. It tugs on your emotions, making you sad and wanting to help. Yet if you were told the reality of the situation and just how many people required help, your reason would kick in and you would question how much help you are actually capable of giving. This is because our brains can’t compute a large amount of victims in the same way we can compute one.

Whilst this is not a new technique and employing an identifiable victim has been widely used by charities, it does make me question our actions. It suggests that we are more likely to sympathise with other people’s tragedy and are willing to help others when we don’t think. We are rational beings and acting on our emotions goes against this. But I don’t think this is a bad thing at all, and the fact that TV campaigns can evoke such deep emotions in us shows that we do care. Maybe we should be thinking with our hearts and not our heads.

In constant competition

What struck me the most was research conducted by various psychologists into the influence of others on our own donations. Sarah Smith studied JustGiving pages and images of females. It became apparent that men donated more money than they normally would if the woman was judged attractive; up to four times as much if other men had already made large donations.

This isn’t exactly shocking news, but it’s not particularly promising for us non super-models of the world. And, I find it interesting, that competition can increase donations by such a great amount. The question is when will we begin to act on our own accord? Or are we forever determined by ‘social norms’ and the actions of our peers?

Personally, I think this competitiveness is embedded within us and we will always want to be the best, and in this case give the most. But I don’t think that the motivating factor particularly matters; if my dad sponsoring me £50 to run a Marathon means that my Uncle will too, then great!

The concept of social norms and comparing ourselves to others is also evident in will making. Over the past two years solicitors involved in a legacy research project asked will makers different questions, firstly ‘If you have been helped by a charity in the past, would you consider giving something back in your will?’ and secondly, ‘Many people choose to leave money in their wills, would you consider doing the same?’.

Those that were asked the second question were more likely to write a charity into their will.

Firstly, I think that this raises a question of ethics - is it fair to prompt people in this way, perhaps making them feel guilty if they weren’t planning to leave anything to charity? Some might go so far as to say it is manipulation. However, I personally think it is completely fair. Although 1/3 of us say that we would like to donate in our wills, only 6.5% do. Bridging this gap could have a major impact on charitable donations.

What does this mean for charities?

These findings won’t come as surprise to most people who work in fundraising. Yet they might act as a reminder of what motivates the public to make charitable donations. Emotive identifiable campaigns are more likely to gain support and donations than those that are full of facts and figures which people struggle to compute.

With will giving, charities are being provided with an exciting opportunity to raise more money and should take it.

The more money raised the better; a bit of healthy competition isn’t a bad thing if it increases the amount of money going into the sector. But whether all charities that work in fundraising can make the most of this is another matter.