You need a new top. You go to a big online retailer, find one you like, and place your order. When it is delivered, you check the quality, the size, and if it makes you look good; if it doesn’t pass these tests, you send it back for a refund. Now you want to make a donation to charity. Unlike when buying a top, you don’t receive anything tangible for your money. You simply have to trust the charity to make a positive impact with your donation. No seeing if it fits, or if it is good quality, and certainly no refunds!

This is why trust is the foundation of our relationship with charities. If the public lose trust in charities, their very existence comes under threat. But where does this trust come from? How does it develop and change over time? At nfpSynergy, we are currently partnering with ACEVO to help their members and our clients to shed more light on these questions. This blog draws on some of the key themes from our first report.

The power of availability

Last year, more than half of the UK public said that they trusted charities. This is no mean feat, given that we live in times when traditional institutions are increasingly viewed with suspicion. However, trust in charities has by no means been stable. At the start of 2018, it dropped significantly as a result of media coverage of unethical behaviour. Many still remember the accusations raised against Oxfam’s workers in Haiti and the treatment of staff at the Presidents Club fundraising dinner. Since then, trust in charities has been slowly recovering.

How do people determine whether they “trust charities”? After all, ‘trust’ is a rather abstract concept. The rational thing to do would be to look inside your head, check how much you trust all the different individual charities you know and then calculate the average. However, this is clearly not what happens. When we asked people about their trust in individual charities one-by-one and averaged the results across more than 100 charities, we got a much a higher figure than when we asked people whether they “trust charities” in general.

Figure 1. The availability heuristic.

This is no surprise. To make broad judgements like this one, people need to rely on mental shortcuts. It seems that in this case, people rely on the so-called availability heuristic. This is people’s tendency to make judgements about large categories based on the first examples that they can think of[i]. When you get asked whether you trust charities, you will probably think of the first few charities that spring to mind and tailor your response accordingly. These are likely to be the last few charities that you have seen covered in the media. When these stories are negative, the overall trust in charities figure goes down.

Why trust falters

One reason why trust in charities is so susceptible to disruption by negative media coverage is that ethical behaviour is the main thing people expect from charities. Businesses are primarily expected to be making profit; therefore, few people feel betrayed when they pursue this goal. For charities, however, it is a completely different story. Charities earn their position in society only through the pursuit of public good[ii].

This is why we were not surprised to find that the belief that charities are ethical and honest is the biggest driver of trust in charities in our recent nine nation study. When people lose this belief, their trust in charities breaks. However, it’s certainly not the only factor that affects trust. As the diagram shows, the other most important attitudes that predict trust are believing that charities are well-run and that they can make a real difference. This points to an important lesson: relying on ethics is not enough. To earn trust, charities need to work on their perceived efficiency and impact too.

Figure 2. The drivers of trust, by relative importance

Source: nfpSynergy international survey, September 2018, nfpSynergy | Base: 6,600 adults 16+, 9 countries

Not too challenging

This is all well and good, but one might wonder – why are some charities trusted more than others? Our data confirms that trust in individual charities varies considerably. What is it that makes your particular charity trusted or distrusted?

It is in human nature to trust things that behave in predictable ways and pursue intelligible goals[iii]. You would be more likely to trust an old reliable coffee machine than a flaky one that sometimes has excellent results but often breaks. In line with this, we found an indication that older and more established charities find it slightly easier to win the public’s trust. There is a correlation, albeit mild, between the age of a charity and its trustworthiness. If you stick around for a while, people will become familiar with you and start trusting you more.

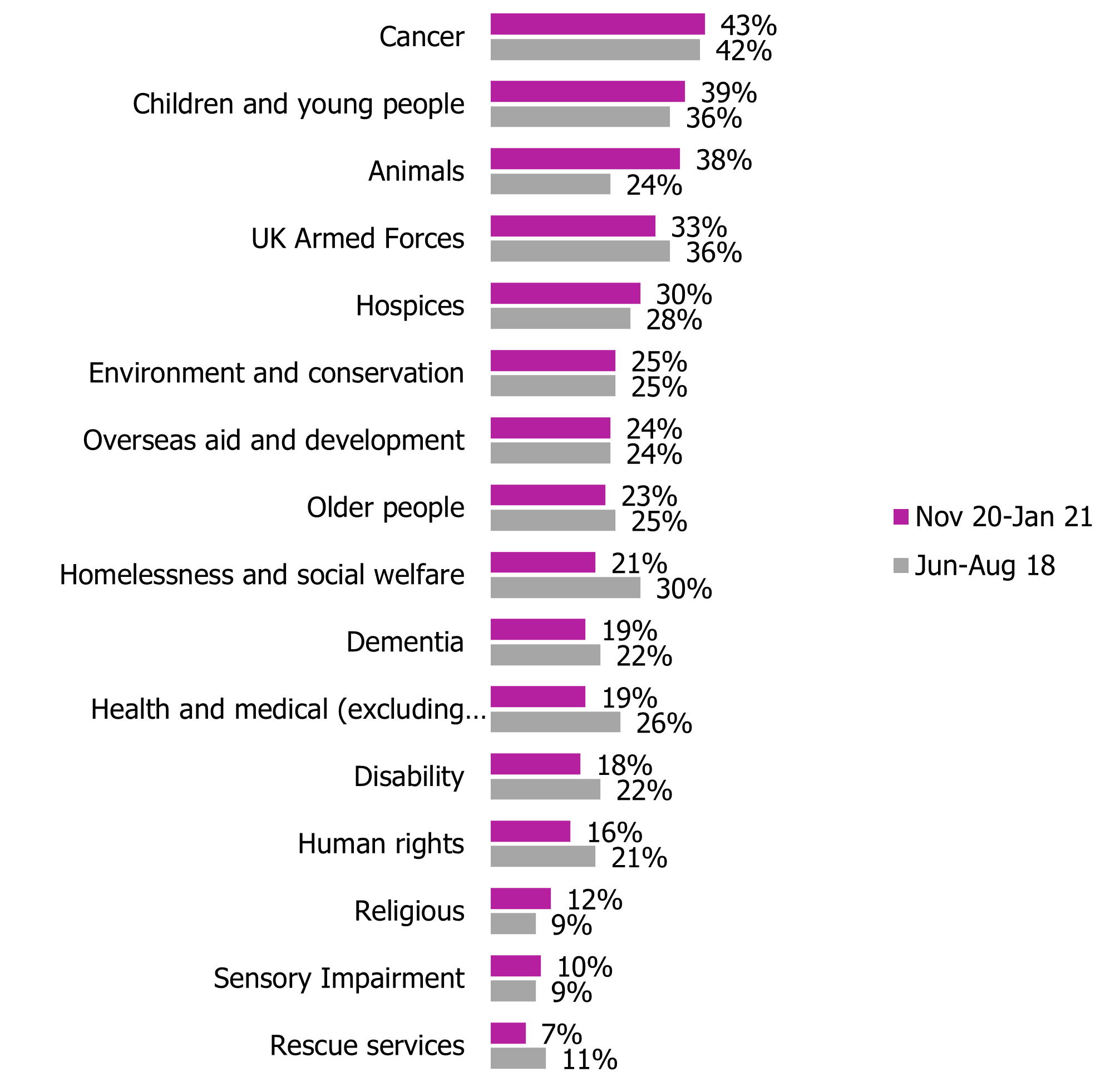

Furthermore, people tend to trust charities whose work they can understand and who do not attempt to question their worldview too much. Charities that help children or work on serious health conditions such as cancer are amongst the most trusted. On the other hand, charities that challenge the status quo and attempt to fundamentally change the way the world works – such as environmental or LGBT+ charities – find themselves at the opposite side of the spectrum. If you venture into a challenging territory, you simply cannot expect to be trusted by the majority.

Conclusion

Trust in charities is a highly elusive matter. This is because it takes a long time to build and a short time to break. Charities need to be wary that people often rely on quick mental shortcuts when they decide whether they trust an organisation, and thus watch out how they present themselves. If you want to be trusted, you need to make it clear that you have the public good in mind and behave in ways that people can understand.