I am of the opinion that a strange myth exists among the left in the UK that charities aren’t and shouldn’t be delivering public services – exemplified by articles like this one (‘Giving is good – but we should never forget that the NHS is not a charity’) from the Guardian. The reality is that charities are, and always have been deeply embedded in the delivery of public services: whether Guardian readers and columnists like it or not. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown (yet again) how important charities are: whether its running food banks, organising volunteering, raising money, looking after the vulnerable or speaking out for beneficiaries.

Broadly speaking, there are three ways that charities get involved in the delivery of public services:

Fundraising and volunteering for public-funded services

During the pandemic the public has cheered for NHS workers and given tens of millions to the NHS. This has come not just from people like Major Tom Moore; over £150 million has been given to NHS charities since the pandemic began. This is nothing new. Great Ormond St Hospital has an income of nearly £100 million to deliver services on the NHS. PTAs raise around £110 million for schools every year. We also fundraise for National Parks, local communities, local playgrounds and much more. Volunteering to deliver public services is equally common, whether its volunteering for the NHS (witness the recent Covid-19 volunteer response), people being special constables or St John ambulance volunteers, and of course, the tens of thousands who volunteer in schools.

Running services that are public services in all but name

Some essential services are run by charities, but could easily be considered public services. Lifeboats, hospices, air ambulances, Macmillan nurses; all are services that many might say ‘should’ be run by government, but are not. It can sometimes seem as though there is no rhyme or reason as to why some services are delivered by charities, while others are delivered through government funding; why should the ambulance on a road by run and paid for by government, but the ones in the sky be paid for by public fundraising? The list of anomalies goes on and on. The reality is that the arrangements work, and charities deliver.

Contracted out running of services

While the previous two areas of public services and charities are many years old, it is public services funded by government and delivered by charities that is a real growth area. According to the NCVO almanac, government provided £10.5 billion to charities in 2000/01 and £16.6 billion by 2009/10. There are some charities whose sources of funding are almost entirely made up of government or statutory income – Turning Point and International Rescue Committee are two cases in point.

Between these three models of charity activities, a whole swathe of the sector is embedded in public services. But what does the public think of that? In our regular tracking of public attitudes, we have asked about how they see charities and public service delivery, and attitudes are mixed.

In 2009 we asked the public - ‘would you be happy for charities to take a bigger role in the provision of public services such as healthcare and social services?” 56% said they would be happy, 16% said they wouldn’t, and 28% said they weren’t sure.

By 2017 the percentage saying they would be happy for charities to take a bigger role had dropped from 56% to 41%, and those saying no had increased from 16% to 21%. It was the ‘don’t knows’ that had increased the most: from 21% to 38%. In other words, a lot more people were unsure whether it was a good idea. It is perhaps not surprising to see this change with a decade of austerity in between the two data points: many people may have seen charities taking a bigger role in public services as a way of cutting costs, rather than improving quality.

We also asked the public whether their decision to donate to a charity would be affected by whether or not the charity also received public funds from the government. Around 65% said it would make no difference, 13% said it would make them more likely to give, 13% said less likely, and the rest weren’t sure. These figures have not changed much since 2009.

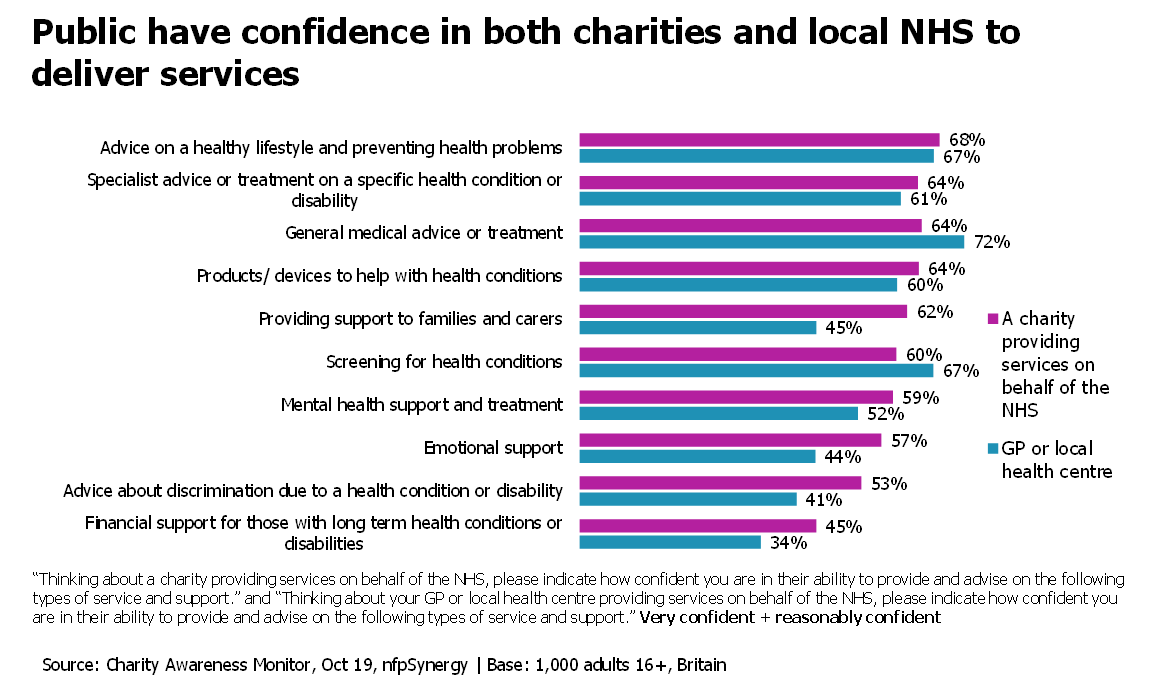

Late last year, we asked a more granular question about public service delivery and charities. The results are below:

What’s fascinating is that from the list of prompts, there are only two areas where the public have more confidence in their local health centre or GP to deliver; the rest are pretty equal or charities are favoured.

Another interesting feature of this question, versus the more general question about public service delivery, is that this more granular question, asking about the specifics of who delivers the service, shows far less public negativity about charities delivering services vs their local NHS. It may also be that the general question about how ‘acceptable’ delivery by charities is teases out a more ideological response, while the more granular second question teases out a more practical response about levels of confidence.

We are asking more question about public service delivery and charities in the near future. Get in touch with insight@nfpsynergy.net if you would like to find out more about this research.

There are three conclusions for me about what the Covid-19 pandemic has shown us:

- Charities are deeply embedded in the delivery of public services in the UK. We fundraise for public services. We volunteer to help deliver public services. These behaviours are deeply embedded in public life, and Covid-19 has highlighted, not changed that. Anyone who care about charities should be deeply proud of how important (and largely unrecognised) charities have been in maintaining the fabric of our society during Covid-19 and before.

- It’s hard to interpret our research as saying the public are against public service delivery by charities. While we don’t have Covid-19 specific research, it’s likely that the events of the last few months have made the public keener, rather than less so.

- One of my favourite quotes is attributed to the venerable Chinese leader Deng Xiao Peng:

‘It does not matter whether the cat is black or white as long as it catches the mouse.’

For me, what matters is not the ideology of who delivers a service, but the effectiveness of that service. Sometimes charities are most effective, sometimes the state, and sometimes private companies. At times of crisis we should worry even less about the ‘colour of the cat’, and much more about the difference that charities are making.