Mind the gap – racial inequalities in the UK

Racial inequalities still exist in the UK. I won’t linger for too long on this – I’m not sure it needs explaining. Nonetheless, recognition of the systematic ways in which racism plays out in the UK has long lagged behind recognition of similar (though qualitatively different) struggles faced by women. Who hasn’t heard of the gender pay gap?

But have you heard of the BME pay gap?

More and more, we’re seeing the ways in which BME people in the UK struggle to gain the same successes as their white counterparts, from schools to universities to workplaces. And institutions are talking about it too. See, for example, UUK and the NUS’s Closing the Gap campaign, aimed at tackling the disparity between the proportion of ‘top degrees’ (first or a 2:1) achieved by white and BAME students.

Differences in volunteering patterns

Volunteering is perhaps not the first area that you would think to analyse when examining racial inequalities in the UK. But volunteering rates vary across groups – we’ve known this for a long time (see, for example, our Volunteering Trend Data from 2017 or our Facts and Figures: Volunteering). Age and social grade show significant variations in volunteering rates: in recent years, young people have become significantly more likely to volunteer, whilst volunteering rates amongst 45-64 year olds have declined.

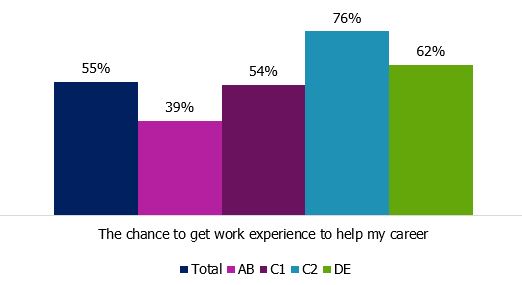

We also know that the reasons that people volunteer vary, and we regularly dig into differences across age, gender and social grade (see our CAMEOs, free quarterly reports on sector context issued to our current CAM clients). For example, as we see in the graph below, “the chance to get work experience to help my career” is significantly less important to people from AB social grades compared to C1, C2 and DE social grades – painting an interesting (read: harrowing) portrait of job opportunities in the UK.

Figure 1. Importance of gaining experience to help one’s career through volunteering, by social grade

“Thinking about your volunteering commitments, how important was each of the following in your decision to become a volunteer” Very important + Quite important

Source: Charity Awareness Monitor, Nov 2018, nfpSynergy | Base: 283 adults 16+, Britain

But what we haven’t yet examined are the ways in which volunteering – and in particular, the motivations behind it - vary by ethnicity. But we know that racial inequality permeates every area of life – including volunteering habits. So let’s delve into it.

Getting on the career ladder: the (unequal) importance of volunteering as a first step

We asked people how important various factors were in their decision to become a volunteer, testing factors such as “the volunteering opportunity was fun” and “a desire to help out in my local community”. And we found significant differences between those who described themselves as white British and those who identified as another ethnicity.

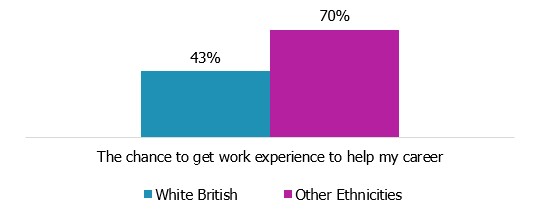

There were two key motivating factors that showed significant differences between white British people and those of other ethnicities: gaining work experience to help one’s career, and maintaining jobseekers’ allowance.

Figure 2. Importance of gaining work experience to help one’s career through volunteering, by ethnicity

“Thinking about your volunteering commitments, how important was each of the following in your decision to become a volunteer” Very important + Quite important

Source: Charity Awareness Monitor, Oct 17 + Nov 18, nfpSynergy | Base: 523 adults 16+, Britain

As we see in figure 2, white British people are significantly less likely to say that their decision to volunteer is motivated by the ability to gain work experience to help their career. In fact, when we break this down further, we see that 34% of white British people said that this was not at all important to their decision making – compared to just 7% of people from other ethnic groups.

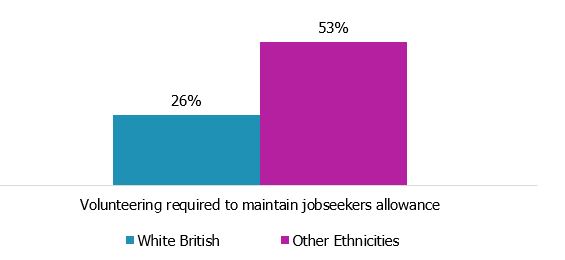

We see these differences re-emerging when we look at the relationship between volunteering and maintaining jobseekers’ allowance. The proportion of people who said that “volunteering required to maintain jobseeker’s allowance” was either quite or very important to their decision to volunteer doubled for people who do not identify as white British in the UK, compared to their white British counterparts. And when we look at how many stated that this was not at all important, 51% of white British people agreed, compared to just 23% of people from other ethnic backgrounds.

You may well look at these figures and simply think “well, poverty is a racialised issue”. You would be right to think this. But what these graphs also show is that ethnicity has an undeniable impact on people’s relationship to voluntary work – and therefore must be considered when examining other factors, such as age, gender or socio-economic status.

Figure 3. Importance of maintaining jobseeker’s allowance through volunteering, by ethnicity

“Thinking about your volunteering commitments, how important was each of the following in your decision to become a volunteer” Very important + Quite important

Source: Charity Awareness Monitor, Oct 17 + Nov 18, nfpSynergy | Base: 523 adults 16+, Britain

Unfortunately, due to the small sample we are unable to break the “other ethnicities” group into specific ethnic groups or demographics within them. This is an important area to expand into, for two key reasons. Firstly, the category “BME” is not a monolith. No-one would say, for example, that the struggles faced by Chinese people in the UK are an exact mirror of the issues faced by Bangladeshi people in the UK. Similarly, the hurdles that many black African women in the UK face are not necessarily wholly shared by their male counterparts. Secondly, people of “other ethnicities” includes white, non-British people – whose experiences will again be different to BME people in the UK. These nuances are certainly areas that we hope to explore further, with a larger sample (of the 523 adults who answered these questions, just 108 were from “other ethnicities”). But this is a clear beginning, and we hope to build on this work in the future to gain a deeper insight into the ways that people’s needs, motivations and behaviour vary, and how this impacts their engagement with charities.

Whilst the above is obviously not great news, historically we know that reporting on the problem is a necessary step to finding solutions. We need to continue pushing for robust understanding of the issues facing BME people within the charity sector – be that as charity employees, service users, donors or volunteers.

If you are interested in conducting research with marginalised or hard to reach groups, get in touch with our Projects team here.